Use this map to explore the three days of unrest that came to be known as the ‘Battle of the Bogside.’ Click on the various plotted points to learn more about the ways in which the Bogside residents, RUC, and British military interacted. Follow the green line to see the area of the city that became citizen controlled, named Free Derry.

Additional contextual information can be found below.

The city of Derry holds weight in both Northern Irish Protestant and Catholic identity. For the latter, it is a center of Catholic solidarity and resistance. For the former, it is the site of a major Protestant resistance to Catholic insurrection. In 1689, a Catholic led army made its way to the city in the hopes of taking it over, but several young Protestant men closed the gates of the city’s walls and refused to let them in.1 The slogan ‘No Surrender!’ has been a part of Northern Irish Protestant culture ever since. It is this action that the Protestant, Loyalist group the Apprentice Boys celebrate every year. In Derry, this parade takes place on the 12th of August each year and, despite the rising tensions in the city, 1969 was to be no different.2

The violent clashes between civil rights demonstrators and the death of Catholic civilians Samuel Devenney and Francis McCloskey that had plagued the city over the preceding months had caused many within the Catholic community to be especially concerned about that year’s Apprentice Boys parade. The celebration itself had always been viewed as offensive within the Catholic community, but this sentiment was especially severe that year. The brazen pronouncements of ‘No Surrender’ were understood as a direct challenge to the growing civil rights movement, and to the idea of equality for Catholics in Northern Ireland more generally. Despite warnings from leaders within the civil rights movement, the Apprentice Boys of Derry insisted on going ahead with their march.3 The RUC called in reserve forces in an attempt to prepare for the clashes that seemed inevitable. Bogside residents, knowing all too well that the RUC was aligned with the Protestant population, began preparing to defend themselves. Neighbors worked together to construct makeshift barricades out of lumber and old furniture in an attempt to deter the procession from entering the neighborhood. Some even built petrol bombs in preparation for violence.4

The trajectory of the procession would take them along the walls of the city-center and, therefore, along the edges of the Bogside neighborhood. Even before the Apprentice Boys’ arrival there, law enforcement and Protestant celebrators had been taunting the Catholic citizenry. This led to young Catholics tossing pennies at the procession, symbolizing the low-income reality of so many of this population, saying “there you are, you can earn it like we can.”5 The focal point of the growing tension was at Waterloo place, a site that had seen sectarian clashes in the past. The RUC had placed crush barriers at the entrance of several streets leading there, in an attempt to keep the Loyalist procession out of the Bogside and keep the Catholic residents sequestered within their neighborhood.6 Though this was done as a means of crowd control, the construction of the barriers actually brought many crowds to Waterloo Place as it was perceived as a form of state control by many Derry Catholics. This sentiment was only amplified by the recent banning of civil rights marches by the authorities in weeks past – why was an Apprentice Boys procession deemed legitimate while a march demanding equal rights was not?

Despite some stone throwing directed at law enforcement, the procession made it through Waterloo square without any major instances of violence. Many have claimed that the restraint exhibited by the RUC there was due in large part to the presence of journalists and camera crews, parties who were notably absent a few blocks away at the junction of Sackville and Little James Street.7 As tensions grew here, the RUC demonstrated less control in their response to the Catholics protesting at these barricades. In the Scarman Report that was issued by the British government following the Battle, it is stated that the RUC’s strategy that day was to keep the Catholic residents sequestered in the Bogside for the fear of them rioting in the center of the city and looting the shopping districts. It should be noted that journalists who were among the Catholic dissidents at the time reported no indication that this concern was warranted.8 Whatever the truth is, or if there even is a single truth when such a significant number of people are involved, what we know at this point is best summed up by Russel Stetler in his 1970 book The Battle of the Bogside: The Politics of Violence in Northern Ireland.

“Two groups confront one another in an atmosphere of tension, recrimination, and abuse. They impute to one another sinister intensions which may be far beyond what is in fact contemplated by either side. Each side sees itself as performing a defensive duty and strives to do so with increasing force. Every casualty suffered reinforces the prejudices concerning the attributed intention. There is no means of extricating oneself from the trap. The longer one maintains the game, the more likely it becomes that one’s opponent will be forced or provoked into carrying out the sinister intentions which he initially lacked. At best, there is an equilibrium like that of a medieval battle, in which victory is not measured in movement, but in the pain and terror which one side can inflict on the other.”

Stetler, Russel, The Battle of the Bogside: The Politics of Violence in Northern Ireland, (London, UK: Sheed & Ward), 1970, 84.

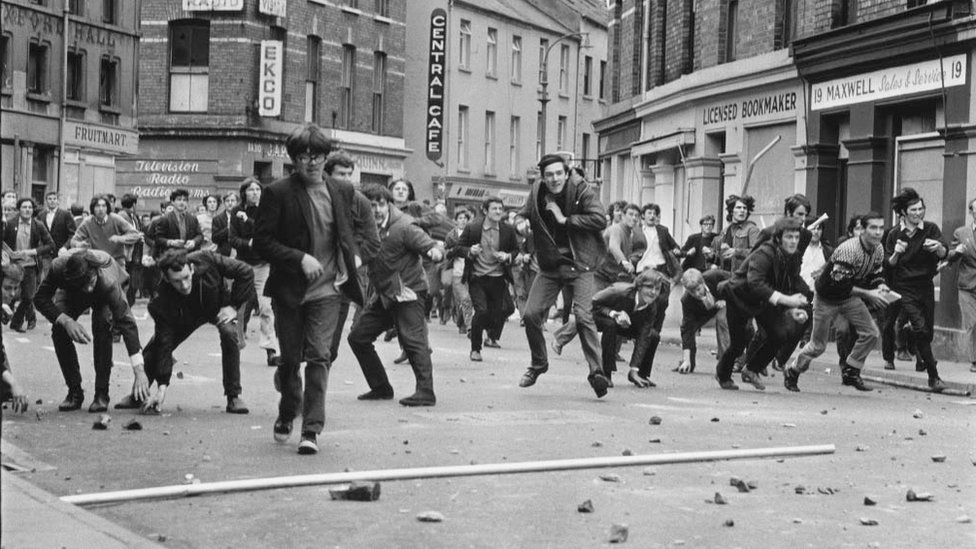

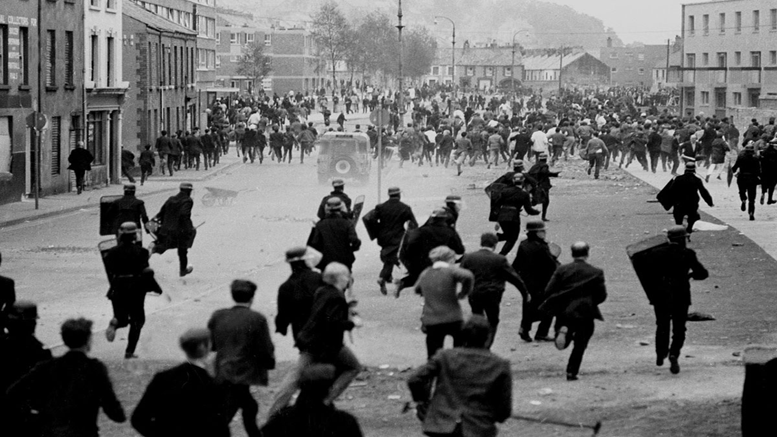

This describes the state of affairs that afternoon, with the tossing of petrol bombs by Catholic residents and the responding tossing of stones by the RUC and Loyalist onlookers. Reports have stated that the RUC officers were going as far as to collect stones on their shields to supply to the Loyalist gangs that were clashing with the Catholic residents.10 At this point, most of the windows of the Bogside houses that lined the street where the procession had taken place had been broken. The RUC had brought in Land Rovers, Hummer Armed Vehicles, and water cannons and they began their efforts to take down the makeshift barricade that Bogside residents had created at Rossville street. As they made their way into the neighbourhood, they were met with Petrol bombs thrown from residents of upper floor apartments. At this point, law enforcement (who were far outnumbered by the Bogside residents) enlisted support from Loyalist gangs.11 Such a decision only validated the Catholic perspective that they were second-class citizens in a country whose government, and by extension law enforcement, favored and took the side of another class of citizens: Protestant loyalists. The invasion of the Bogside was felt as an epitomization of this reality.

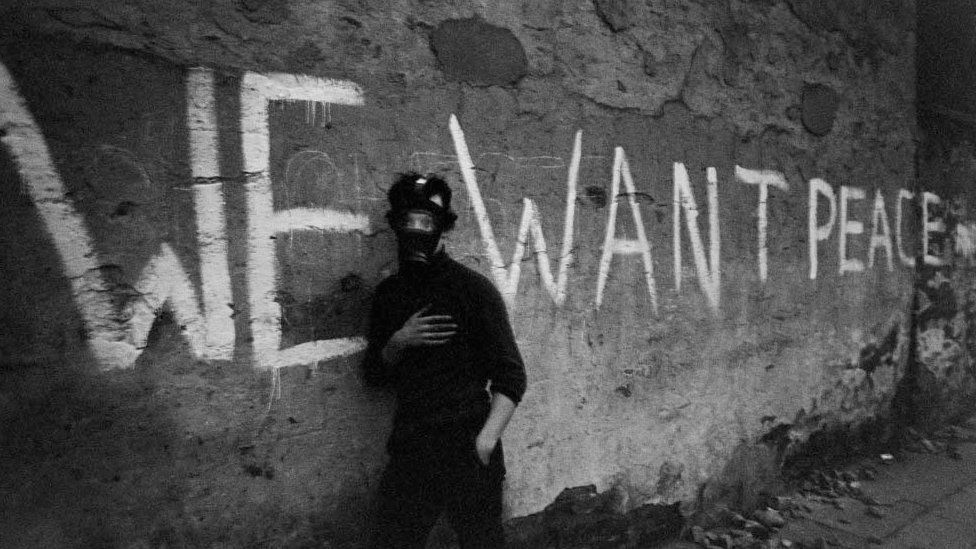

This was only bolstered by the RUC’s decision to use CS-gas, commonly known as tear gas, which was only possible because of an alteration by the Minister of Home Affairs on the use of tear gas just three days earlier.12 This would be the first time that representatives of the British government used tear gas on its own citizens, a practice that they had reserved for use on colonial subjects or during times of war.13 There is debate over whether an adequate warning was given to the crowd of Bogside residents. Either way, canisters of the gas were fired into the crowd and, as District Inspector Armstrong puts it, “It was very effective and I was delighted to see it.”14 The launching of tear gas canisters and the returning of petrol bombs continued throughout the night and well into the next day. This escalation in conflict led to the Northern Irish Prime Minister John Hume calling upon Westminster in London to send in the British military as reinforcements. NICRA also released the following statement…

“A war of genocide is about to flare across the North. The Civil Rights Association demands that all Irishmen recognize their common interdependence and calls upon the Government and the people of the Twenty-six Counties to act now to prevent a great national disaster. We urgently request that the Government take immediate action to have a United Nations peace-keeping force sent to Derry, and if necessary Ireland should recall her peace-keeping troops from Cyprus for service at home. Pending the arrival of a United Nations force we urge immediate suspension of the Six County Government and the partisan RUC and B-Specials and their temporary replacement by joint peacekeeping patrols of Irish and British forces. We urge immediate consultations between the Irish and British Governments to this end. Time has run out in the North.”15

Northern ireland civil rights association, 1969

Bernadette Devlin and Eamonn McCann, two civil rights activists in leadership positions in Northern Ireland, issued the following joint statement…

“The barricades in the Bogside of Derry must not be taken down until the Westminster Government states its clear commitment to the suspension of the constitution of Northern Ireland and calls immediately a constitutional conference representative of Westminster, the Unionist Government, the Government of the Republic of Ireland, and all tendencies within the civil rights movement.”16

Bernadette Devlin & Eamonn Mccann, 1969

The then Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Jack Lynch went on television to announce that Ireland would be stationing field hospitals at the border with the North to aid injured citizens. He stated…

“It is evident that the Stormont Government is no longer in control of the situation. Indeed, the present situation is the inevitable outcome of the policies pursued for decades by successive Stormont governments. It is clear, also, that the Irish Government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse.”17

Taoiseach jack lynch, 1969

These responses by leadership from various institutions in various countries demonstrates the severity of the situation at hand. One side viewed the fighting as law enforcement’s attempt to control a group of dissident citizens. The other saw a nation state’s suppression of a minority population through lethal force. Both sides, however, could agree on one thing: the state of affairs was becoming increasingly grave and some sort of resolution was urgently necessary. Check out the map below to explore the RUC’s invasion of the Bogside neighborhood.

Map Sites

B Specials Station

Little James Street British Army Barbed Wire Barrier

Waterloo Place British Army Barbed Wire Barrier

Creegan Street British Army Barbed Wire Barrier

B507 British Army Barbed Wire Barrier

Notes

- Hewitt, Christopher. “Catholic Grievances, Catholic Nationalism and Violence in Northern Ireland during the Civil Rights Period: A Reconsideration.” The British Journal of Sociology 32, no. 3 (1981): 368.

- Ibid, 366.

- Stetler, Russel, The Battle of the Bogside: The Politics of Violence in Northern Ireland, (London, UK: Sheed & Ward), 1970, 25.

- Ibid, 42.

- Ibid, 67.

- Government of Northern Ireland’s Report of Tribunal Inquiry, Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969, by The Honorable Justice Scarman, Volume I, Belfast, UK: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1972. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Stetler, 84.

- Stetler, 82.

- Stetler, 97.

- Stetler, 101.

- Linstrum, Erik. “Domesticating Chemical Weapons: Tear Gas and the Militarization of Policing in the British Imperial World, 1919–1981.” The Journal of Modern History 91, no. 3 (2019): 557–85.

- Stetler, 112.

- Wallace, Martin, Drums and Guns: Revolution in Ulster, London, 1970, 4.

- Ibid.

- White, B. John Hume: Statesman of the Troubles, Belfast, 1984.